When Jim Rowan purchased his very first box of bees, he was only 10 years old.

Beekeeping wasn’t a part of his family’s upbringing, nor did any teacher or other mentor in his life instill in him a love for the unusual hobby. Instead, while working on a school assignment, the now-retired insurance agent and banker from Sumner County stumbled onto an encyclopedia entry while searching for a topic to write about.

The backstory of the busy and industrious honeybee fascinated the young boy, and he went in search to learn more about these curious creatures. Less than an hour’s drive away in Wichita, Jim found a local beekeeper with honeybees and supplies for sale to start his fi rst colony.

At that time, he purchased two brood chambers (a single-level box that contains the queen and all the eggs she will lay), two honey supers (a box placed on top of the hive that is used to collect honey), and a package of busy bees, for only $10 a piece.

“Those same two hives today would have been $400,” Jim explained. Jim’s wife and small business partner, Sharon, interjected. “This was 66 years ago,” she said. Her response must have stung. “She loves telling my age,” Jim replied with a laugh.

A Buzzworthy Backstory

Jim and Sharon have operated their unique storefront, Rowan’s Honey Shop, in Norwich for nearly two decades. However, their love and devotion for the honeybee spans many years before that.

“I tell everyone she married me for my bees,” Jim said, lovingly. It’s true, Sharon admits. After the couple married in 1967, Sharon, who grew up in Hutchinson and met Jim through her college roommate from Norwich, came on board to the beekeeping business. Jim taught his “city girl” everything she now knows about the honeybee: how to start new colonies each spring, how to care for the creatures, how to build new hives from existing colonies, how to extract their sweet fluid, and more. As they started a family and raised three children together, she took it upon herself to come up with clever and delicious ways to utilize Mother Nature’s sweet syrup in the kitchen, too.

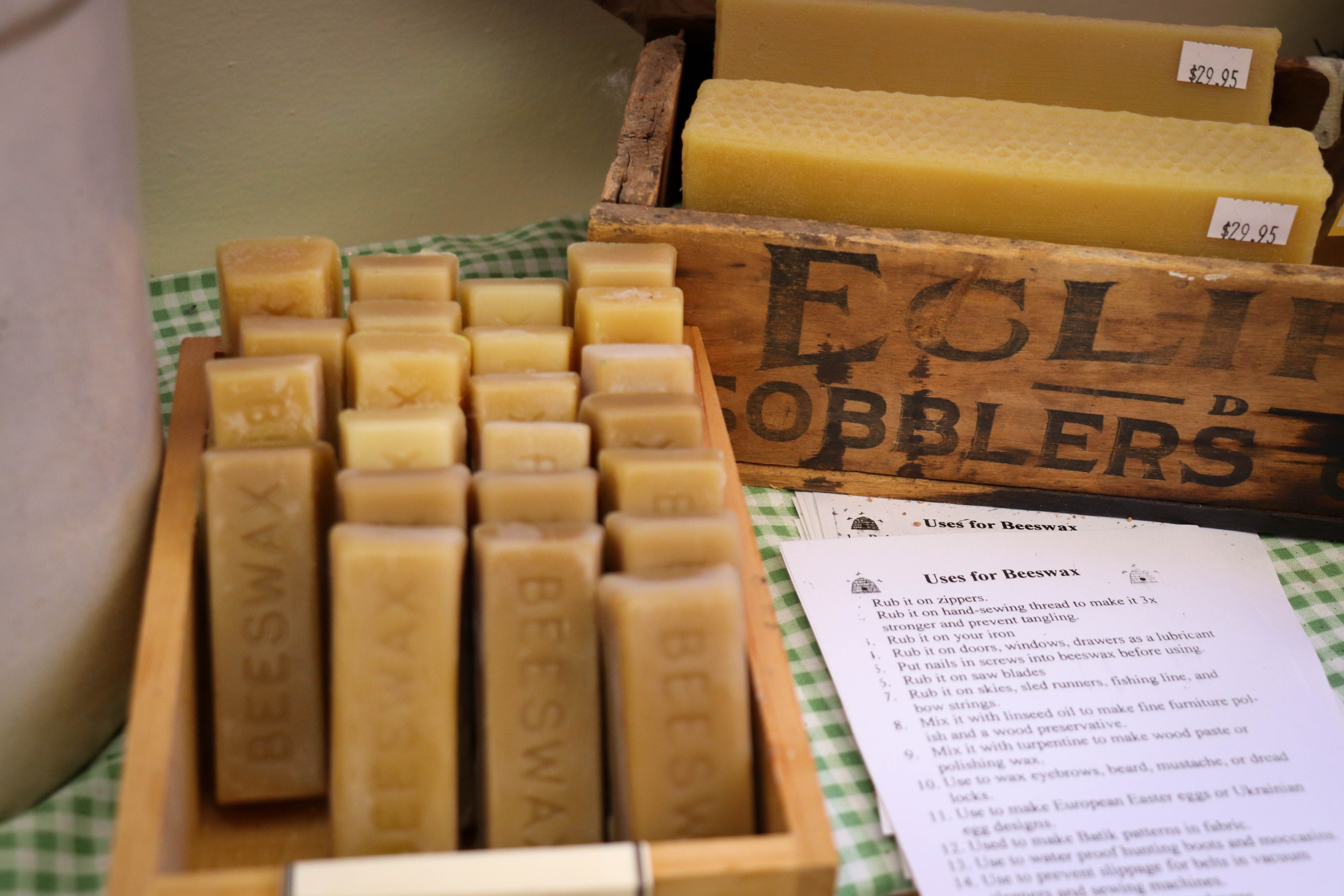

Inside their quaint mom-and-pop shop at 218 N. Main is a homegrown set of products that share a single trait: everything sold inside either contains honey or boasts ingredients belonging to the honey-making process: beeswax in the shoe polish, dried pollen sold in jars and used for allergy relief, and natural honeycombs for spreading on breakfast toast and chewing like gum once all the honey’s gone.

Alongside these goods are the everyday edibles their neighbors across central Kansas and other out-of-town fans come back for: honey apple salsa, honey barbecue sauce, honey horseradish mustard, spun (or creamed) honey infused with a variety of flavors, and — of course — jars and bear-shaped bottles of the sweet, sticky substance that has been so carefully and lovingly extracted from their bees.

Always meant as a hobby, the retired couple (him from finance and her from teaching) now spend most days minding around 200 beehives, working in the kitchen in the back of their shop to craft their concoctions, and teaching people from all walks of life how to start their very own bee operation.

While they’re only advertised as open on Fridays and Saturday mornings, they don’t want to miss any budding bee enthusiasts. That’s why the couple tries to make themselves available almost every day of the week.

“We have so many out-of-towners. If someone drives all that way, I want them to be able to contact us,” Sharon said, adding that their phone number is on the front door. “We’re here almost every day working, maybe not all day, but part of the day. And anytime we’re here, we’re open,” she added.

What All the Buzz is About

An apiary, a place where bees are kept for their honey, generally consists of several hives. The Rowans’ 200 or so hives are spread out across at least four Kansas counties: Sumner, Kingman, Harper and Sedgwick. A good hive will often house between 80,000 to 100,000 honeybees, putting the number of creatures under their care in the tens of millions in the spring and summer.

Oftentimes, the couple will even transport their well-populated hives to areas where farmers or large-scale gardeners want to capitalize on the precious pollination process. Apple orchards, for example, are 100% dependent on bees to produce high yields, according to Jim. So it’s worth the orchardist’s time and money to bring the bees close to his or her apple blossoms, even if for a short period of time. It’s a labor-intensive job, one the Rowans charge for when heavy boxes of hives must be loaded and unloaded repeatedly.

However, it’s necessary because there aren’t enough honeybees in the wild. Many decades of using pesticides, loss of habitat, climate change and disease have all contributed to the rapid decline of these natural pollinators — not only honeybees but also butterflies, beetles, bats and birds. That’s bad news for the planet and its biodiversity, but worse news for our food supply, according to the Rowans.

“Most people don’t realize that one out of every three bites of food you take is thanks to a honeybee,” Sharon said. “But now, there’s been a lot more publicity about bees being in danger, so people are becoming a lot more aware of it.”

A national movement about the dangers our pollinator pals face is growing. That’s why pollinator gardens that are lush with nectar- and pollen rich flowers and plants are becoming more commonplace in community parks, gardens and backyards. Growing interest in beekeeping classes, which are taught by the Rowans at both their shop in Norwich and at Wichita State University, is also at an all-time high. In fact, their students come from all socioeconomic backgrounds — doctors, lawyers, teachers and more.

Their continuing education classes are taught in the early spring, when the business of beekeeping begins, and all the supplies needed to start and maintain a hive can be found right inside Rowan’s Honey Shop. “And we have every age — from young kids to retired folks like us,” Sharon added.

Sticky Business

When Jim brought home his first set of beekeeping supplies as a young boy, he observed his bees every single day with only a makeshift veil, he said. When the honey came that first year, he cut it out of the combs, collected it in a large bowl, and went to work with a potato masher. A novice beekeeper, Jim used cheesecloth to strain the golden liquid. It was a learning experience for the young boy, who eventually ended up with honey all over his mother’s kitchen.

“She said you can’t do that ever again,” Jim said.

“Everything you touch in here is sticky!”

The next year, as Jim’s knowledge in his newfound activity grew, he collected discarded bottles around his neighborhood for 3 cents a piece. He purchased a package of bees that came in the mail — $25 from the Sears Roebuck catalog — and with another $5, a used honey extractor, a device to collect honey using centrifugal force.

It’s the same tool that beekeepers use today, albeit smaller and less modern, to extract the honey without destroying the honeycomb. Of course, even with today’s modern tools and supplies, the business of beekeeping can still be “pretty sticky.”

“We tell beginning beekeepers, you’ve got to remember, a drop of honey will cover an entire kitchen,” Sharon added and laughed.

Busy, Busy Bees

Today, the Rowans order their young bees close to the start of each year. They come on a semi-truck from California and are sold in packages. Each 3 pound package costs somewhere between $150 and $170 and contains enough bees to start a colony that will survive, multiply and flourish. Every bee — male or female — has a very specific role, according to the experts.

Working together, the colony builds and maintains hives, reproduces and raises young, regulates the inside temperature, and collects and stores food in the form of honey. Only one queen per hive can exist, and she lays over 2,000 eggs a day, actively selecting which will be male and which female.

“A drone is a male bee — he has no stinger. He has one purpose and one purpose only — to mate with the queen in midair. This rips him wrong side out, and he falls to earth — dead,” Jim explained.

Unlike the short and tragic life of the male drone, the females — primarily worker bees — run themselves to death, often in as little as two to three weeks in the summer.

The bees come and go from the hives as they please to fulfill Mother Nature’s primary function. That is, pollination is needed for plants to reproduce and the bees also benefit, using nectar and pollen for their own food source. After being carried back to the hive, the pollen and nectar is broken down into simple sugars and stored inside the honeycombs. Only the bees know when their honey is ready, capping each individual comb with beeswax that is secreted from their abdomens.

This also tells humans that the honey is “cured” or ready to be consumed, normally during the hotter months of July and August, according to the Rowans. Honey extracted prior to being capped is “green” and would make us very sick if consumed.

“Man can’t make honey because they don’t know when to put that wax cap on. We melt that beeswax down, and it’s worth even more than the honey,” Jim explained, adding that it takes 10 pounds of honey to make a pound of wax.

In fact, pure beeswax has many uses including strengthening sewing thread, lubricating wood furniture and tools, and is mixed with additional ingredients to make some of the other items sold in their store: shoe polish, lip balm, soap and other products. Alongside these items is the pure golden syrup that wouldn’t be possible without the heavy lifting performed by honeybees, primarily by the working females inside each colony.

“Remember, a male can’t feed himself, he can’t sting you, and he can’t gather nectar,” Sharon said. “I always tell the schoolkids that the (male) drones are the cheerleaders. They sit in their chair all summer and say ‘Girls, you’re doing a great job — keep up the good work!’”

Meant to Bee

Until about a decade ago, the shop where the Rowans now sell their honey used to be the post office in Norwich, a community of about 500. Prior to that, starting in 1980, the couple sold honey out of the back door of their home. Despite demand for their product, they took a long break from the business starting in 1982 to raise their three children and focus on their full-time jobs, only fully returning to the honey hustle again in the early 2000s.

Today, their knowledge and expertise are well known in their quad-county area. For example, when folks see bee swarms in their local area, their first call is to the Rowans. Swarming is a colony’s natural means of reproduction — when a single colony splits into two or more — and can most often be seen in large clusters on tree branches. A photograph of one of the largest swarms the couple has ever been called to — on Main Street in Harper — hangs on the back wall of their shop.

“That was an exceptionally big one. We caught it, put it in a hive, and took it home,” Jim said, explaining that all he had to do to get the bees to cooperate was shake the tree branch, which allowed him to dump the bees into a bucket before pouring them into an empty hive.

“(Sharon) says when I catch swarms, I make it look too easy,” Jim added, joking.

Believe it or not, when bees are swarming, they are often more docile than normal because their primary motive is finding a new home as opposed to protecting their young or defending their honey stores, according to the bee experts.

On the very same wall inside their honey shop hangs another photograph, this one a portrait of their daughter, Jackie, wearing her 2003 Kansas Honey Queen crown. The youngest of their three adult children, the Kansas State University graduate and student of bakery science has often helped her parents develop new ideas and products for the family business.

In fact, the Rowans have even discussed handing over the keys to their three children, two sons who live out of state and their daughter who lives closer to home.

Between their children and many grandchildren, the Rowans are hopeful that they’ll be able to pass on their love for honeybees and the creatures’ golden gift to their community for generations to come.

“(Jackie) was only three years old when she was running the mixer at home. As a kid, you think she’d pull it up and splatter, but she never did,” Jim said, referring to his grown daughter. “Her daughter, our granddaughter Elizabeth — she’s only three — and she’s the same way. She loves to help grandma cook — and grandma loves it, too.”